|

|

|

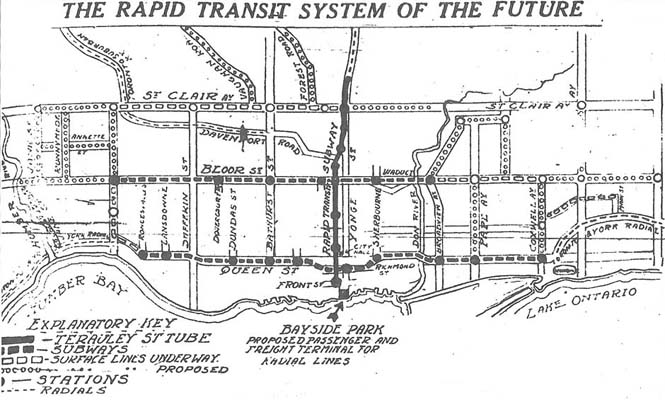

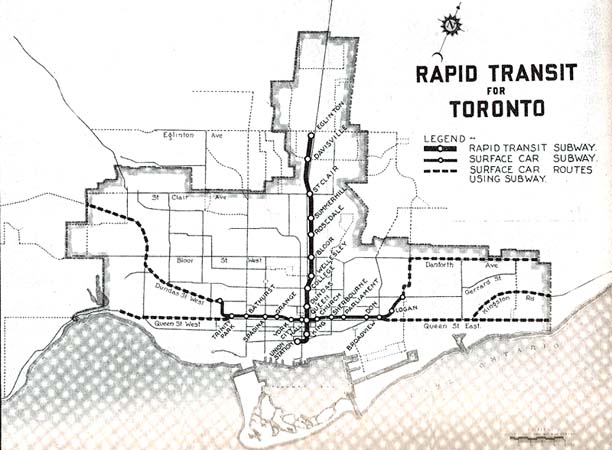

A History of the Queen and Downtown Relief Line Subway ProposalsIntroduction Early Proposals The Post World War 2 Proposals 1985's Network 2011 Plan and 1991's Let's Move Recent Resurgence of the Downtown Relief Line Conclusion IntroductionThe history of subway construction in the City of Toronto long predates the opening of the original Yonge Subway from Union to Eglinton in 195419. Toronto has had a century's worth of subway proposals go unfulfilled: had these plans come to fruition, our city could look significantly different. This section will look at the history of these plans for both subways along Queen Street, as well as more modern plans for the Downtown Relief Line. Early ProposalsThe earliest serious proposal for a subway in Toronto dates back to 1909, a plan that was to be mirrored many times for several years. City Engineer Charles Rust prepared a report with the Kearney High-Speed Railway Company of London on the feasibility of the construction of subways in the city of Toronto59. Rust studied the idea of a subway along Yonge from Front to Summerhill, one along Queen from Roncesvalles to Balsam Avenue, and one under King from Roncesvalles to the Don River. The cost was estimated to be $23 million; Rust determined that Toronto, a city of only 300,000 people at the time, was too small to undergo such a venture58. Meanwhile, the Kearney company proposed a Yonge line from Front to Eglinton, and a Queen line from East Toronto to Dufferin, where it turned north on Dufferin to Dundas and on to West Toronto59. Toronto was displeased with the service of the Toronto Railway Company at the time, and saw the opportunity to build a competing service as a way to show its displeasure56. A report was drafted that went before council estimating the cost of only the Yonge subway at $5,386,870 (approximately $100 million in 2009 currency)58,87. The estimate and specifics of the plan were not well publicized however, and may not have been well understood by the public164. Nevertheless, on January 1st, 1910, a referendum was held asking voters the question: Are you in favour of the City of Toronto applying to the legislature for power to construct and operate a municipal system of subway and surface street railway, subject to the approval of qualified ratepayers?56 Despite this question not specifying cost, and details being fairly vague, the citizenry voted in favour of the measure, 19,268 to 10,69720. Unfortunately, nothing was done as George Geary, who opposed subway construction due to its cost, won the mayoralty. The idea of subway construction did not immediately die, however. On May 25, 1910, another report was commissioned from the firm of Jacobs & Davies. Released on August 25, 1910, the report studied the possibility of three subways. One subway was to run up Yonge St. from Wellington to St. Clair, one going northeast from Front and Yonge to Broadview and Danforth, and one going northwest from Front and Yonge to Dundas and Keele. The cost for this plan was estimated to be $23,470,000 (Approximately $450,000,000 in 2009 currency)63,87. Despite costing out all the lines, it was recommended that only the Yonge line be constructed first, until roads leading northeast and northwest that the subways would be constructed under were built. In 1911, Assistant City Engineer E.L. Cousins agreed that the lines could not be constructed without the roads, and the roads may not have been feasible. In turn, he suggested running three subway lines: one being the Yonge line, another along Queen from High Park to Woodbine Avenue, and another on Bloor from High Park to Broadview. The city tendered offers to build the tunnel up Yonge Street, and the cheapest offer to come in was $2.6 million (Approximately $50 million in 2009 currency), not including track, signals, power, or rolling stock, which could have more than doubled the cost. The city's voters turned down this proposal, by a margin of 11,130 to 7,697 20,56,87. This would be the end of any serious subway talk for more than thirty years. The Post World War 2 ProposalsThe TTC became convinced that development of Toronto would increase dramatically after the war, and in 1941, drew up a proposal for two streetcar subway lines. One was to travel up Bay from Front to just past Bloor, where it would curve over to Yonge and continue up to St. Clair. The other would run beneath Adelaide, Richmond, and Queen from Trinity-Bellwoods park to Logan Avenue. This plan was submitted to the City of Toronto on January 22, 1942, but was turned down as it was considered "too complicated."20,59. When the TTC reworked their plan, they came up with a "rapid transit" subway on Yonge running from Union Station to Eglinton, and a streetcar subway running in an open trench on the north side of Queen behind the buildings from Trinity-Bellwoods to Logan, with the section between University and Church built in a tunnel59,115. On New Year's Day of 1946, Torontonians were asked:Are you in favour of the Toronto Transportation Commission proceeding with the proposed rapid transit system provided the Dominion government assumed one-fifth of the cost and provided that the cost to the ratepayers is limited to such amounts as the City Council may agree are necessary for the replacement and improvement of city services? Citizens overwhelmingly voted in favour of this proposal. Though federal funding was promised in 1945, squabbling between the provincial and federal government meant the funding fell through. This meant the City had to build the project themselves; thus they decided to build the Yonge subway first, leaving the Queen subway to be built at a later date18. The Queen subway was not forgotten about, however. When constructing Queen station on the Yonge line, a roughed-out shell of the proposed City Hall Station on the Queen line was constructed beneath Queen Station. This ghost station was built at a cost of $500,000 and remains to this day, but has never seen service115. When the Yonge subway was completed in 1954, the TTC chair called for construction to start immediately on the Queen line, but quickly began to change their minds. The city was growing northward, and the Bloor-Danforth streetcar route was becoming more and more crowded. Alan Lamport and the TTC decided a subway along Bloor-Danforth made more sense, and began pushing for it. Fred Gardiner and the Metro Planning Department, on the other hand, preferred a route that ran under Bloor from Keele only as far as Grace, where it would curve south to Queen, then east on Queen to Pape, where it would curve back north to Danforth, then east to Woodbine. Interestingly, this route proposed by Gardiner and Metro is strikingly similar to modern Downtown Relief Line proposals59. Eventually, Lamport won out and the Bloor subway was built. When the Bloor-Danforth line opened in 1966, this still did not kill talk of the Queen subway. The 1966 Official Plan still had the line shown as a subway from Greenwood to Roncesvalles, but the TTC were starting to believe it was not nearly the necessity it once seemed to be, with the Queen streetcar carrying only 2/3 of the passengers the Bloor-Danforth streetcar did prior to the subway opening115. In 1968, the TTC released a report entitled "Queen Street Subway for Streetcar Operation" that discussed the possibility of a subway from Sherbourne to Spadina along Queen, which would cost $37 million ($222 million in 2009 currency). The report conceded that this solution would simply keep the streetcars out of traffic, but would not increase capacity. The report determined that when a subway was to be built for Queen Street, it "[…]should not be in the form of a downtown underground streetcar tunnel but instead should be a full subway, extending from about Donlands Station on the Bloor-Danforth Subway to the Roncesvalles area."117,87. It was these plans that saw the Queen subway start to morph into the shape of the Downtown Relief Line, as noted by a studied route in the report. It is to be noted that the staff of Metropolitan Toronto Planning Board have recently completed a report on rapid transit priorities for Metropolitan Toronto - 1968. The report recommends, "further study of Queen Street Subway extending from an easterly terminal on Greenwood Avenue and O'Connor Drive, South on Greenwood to Queen Street, West on Queen Street to the Weston rail line at Dufferin Street, and from that point in a North-Western direction on the rail line to a Western point at about Islington Avenue."117 In 1973, the TTC approved the construction of the Queen line from Humber to Greenwood, at an estimated cost of $400 million ($1.9 billion in 2009). The provincial government was expected to pay for 75% of the line, but they refused to commit any money until a Metro Toronto review of transportation needs was completed. This review, released in 1974, stated that there was no immediate need for a Queen subway, and relieving congestion at Bloor-Yonge could be accomplished through other means115. Though this put an end to the idea of a subway along Queen Street, the idea of the line and the discussion of relief of Bloor-Yonge station would be prophetic for a new plan a decade later. This plan would not see a subway along Queen Street, but further south, where planners realized there was more potential for growth than along Queen115. 1985's Network 2011 Plan and 1991's Let's MoveThe first discussion of a Downtown Relief Line began in 1982, when TTC planners realized that the Yonge subway was overly congested and an alternative was required. The planwas very unpopular amongst politicians as it specifically went against the City of Toronto's official plan, which was trying to move office growth out of the city. In fact, a 1977 city policy was put in place to stop any new rapid transit construction from occurring in the downtown158. Despite this policy against the line, in 1983 City Council voted to have the TTC and the Metropolitan Planning Department do a formal study on the Downtown Relief Line, entitled the "Downtown Rapid Transit Study"82. Rather than simply following the historical recommendation of a route along Queen Street, the study noted that Toronto's downtown, notably the financial district, was shifting further south, and one half of new proposals for office space were actually south of Front177. In the study, they note that Queen is too far north of the Financial District, and would not at all serve the railway lands development (Cityplace). It also dismisses running the track along the railway lands as being too far south of the Financial District. Overall, the final recommendation of the report was to run a subway from Pape south to Eastern, then west to the railway tracks, where it would follow the tracks to Union Station, then continue along Front St. to Spadina Ave. The alternative plan was to travel entirely along Front and Wellington to Spadina177. While newspaper reports had the line estimated at $400 million in 1982 ($814 million in 2009)100, the new report set the cost at $568 million ($1 billion in 2009)87. The trip would take 12 minutes from Pape to Spadina in off peak hours, and 15 seconds more during peak hours177. With the TTC and Metro Planning having determined they needed this line, they released the study in 1985, but only publicized it as part of a bundle of new lines called "Network 2011". On May 29, 1985, the TTC released plans to the media for Network 2011, a $2.7 billion ($4.9 billion in 2009) 28-year plan to build a subway along Sheppard Ave., a subway along Eglinton Ave., as well as the Downtown Relief Line, which was to be constructed second after Sheppard between 1994-199897. Despite these plans, politics soon got in the way of construction. Councillors from Etobicoke and York soon started uniting to push the Eglinton line ahead of the Downtown Relief Line in terms of priority23. Even with the political wrangling, in the end it would not make much of a difference, as the new Liberal provincial government was wary of the price tag which had risen to $5 billion ($7.6 billion in 2009), and put the plan under review. The Liberal government soon came up with their own plan, called "Let's Move" which left out the Downtown Relief Line entirely20. Another review followed with the subsequent NDP government, and the Conservative government after that put a stop to almost the entire NDP plan. Ultimately, years of planning resulted in nothing but a truncated Sheppard line, with the Downtown Relief Line relegated to the history books. Because of a drop in ridership experienced during the 1990's, there was no longer a need for the line, and suburban subway expansion received the bulk of the attention172. Recent Resurgence of the Downtown Relief LineWith the internet allowing for a freer exchange of information, transit enthusiasts began actively discussing the possibility of reconsidering the Downtown Relief Line. Chatting on forums and social networking websites finally attracted the attention of the media in 2008, when a National Post story caught on to the groups and asked TTC Chair Adam Giambrone about the possibility of the line in the future. Giambrone called the line a "{…] good idea" but said that it wouldn't receive serious consideration until 2018, noting that the Spadina, Yonge, and Scarborough RT extensions all had greater priority15. In late 2008, Metrolinx, the newly created regional body to co-ordinate transportation for the Greater Toronto Area, released a report entitled "The Big Move", which outlined a $50 billion plan for Toronto and surrounding regions. In it, there is a brief mention in the 16-25 year plan of a "new subway service in the King/Queen corridor in Downtown Toronto [that] will provide relief to the Bloor/Danforth subway line and greatly improved service in the downtown core."17. The plan did not go into further detail, but this was enough to get the Downtown Relief Line back on the media's radar screen. Shortly after the release of the report, Metrolinx Chair Rob MacIsaac said this about the Downtown Relief Line: The so-called DRL or the Queen line is a very long-term project and I think both Metrolinx and the TTC are likely in agreement that that would likely be a subway, but it's really so far off in the future that I don't think anyone's too worried about debating it76. Clearly although it was mentioned in The Big Move, it was still not seen as any sort of priority, let alone a necessity. Though this lack of foresight was occasionally criticized98, it was not until late January of 2009 where a big step occurred to prioritize the line. On January 28, 2009, City Council, led by councilor Michael Thompson, voted to ask Metrolinx to give a higher priority to the Downtown Relief Line, putting it above a Yonge extension that would add riders to a system already at capacity165. Though Metrolinx did not change their plan, Councillor Thompson continued to push the line, submitting a cost analysis of the line to Metrolinx explaining how not building the line could wind up costing the city more money75. Councillor Thompson's pushing of the line clearly had some influence, as TTC Chair Adam Giambrone, who less than one year ago said that the Downtown Relief Line would not even be considered until 2018, made the decision in August to have an analysis of the line begin in the fall of 2009, with public consultation starting in 201075. Rough estimates of the line to Bloor have been given at $2.1 billion for the section east of Spadina, and $900 million for the section west of Spadina prior to any in depth study being done139. Unfortunately, due to budget constraints, in October of 2009, this study was indefinitely deferred75. ConclusionThe Downtown Relief Line is back in the minds of planners, the media, and the public, but this and similar plans have come a lot closer to reality before and still the city has been left with nothing to show for it. Pressure on the upper levels of government needs to be maintained; Yonge is getting more congested every year, and the areas the Relief Line would pass through are being rapidly developed. The reality is this: the more time passes, the more this line will cost the city. After a century of trying to build some incarnation of this subway with no success, it is time to do whatever it takes to get it constructed sooner rather than later, otherwise the day may never come. Image SourcesFrom top to bottom:

|